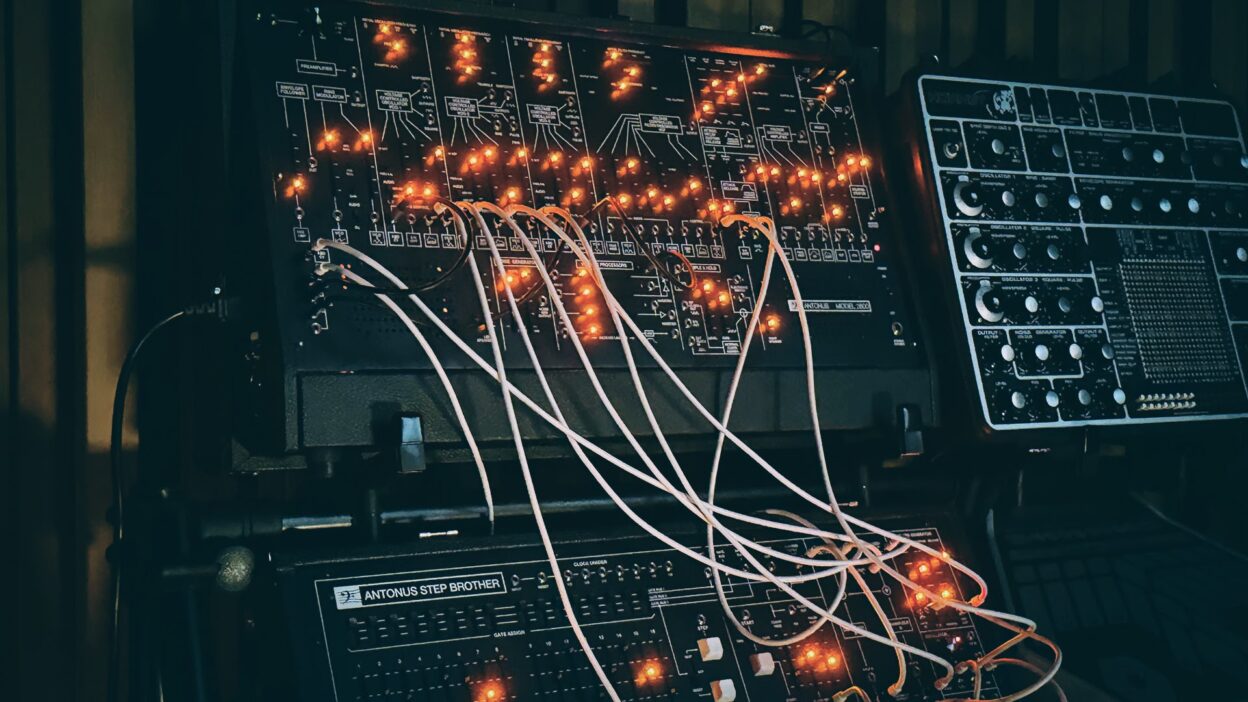

At 3 AM, while the world sleeps, I’m turning knobs on a 50-year-old machine, chasing a sound that exists somewhere between memory and imagination. Today my studio is dark except for the glow of VU meters and the soft amber light from the 2600’s sliders.

You might be thinking I’m about to launch into another “analog is warmer” sermon. Trust me, that’s not where this is going. What I want to share is why, after two decades of making music with everything from jew’s harp to modular systems the size of refrigerators, I chose to write about the 2600 first.

I used to lose entire evenings scrolling through preset banks, A/B testing compressor plugins, getting lost in endless submenus. With the 2600, there’s nowhere to hide. You face the machine, and it faces you back: just you and the voltage. Every sound exists only in that instant unless you commit to recording it. This forced immediacy cuts through the overthinking that plagues modern production.

Here’s where it gets interesting: this constraint breeds a different kind of creativity. When I work with the 2600, I’m not thinking about matching reference tracks or hitting specific frequency targets. I’m listening – really listening – to what’s emerging from the speakers. The machine teaches you to trust your ears again, to follow the sound wherever it wants to go. The song writes itself when you stop trying to force it into predetermined shapes.

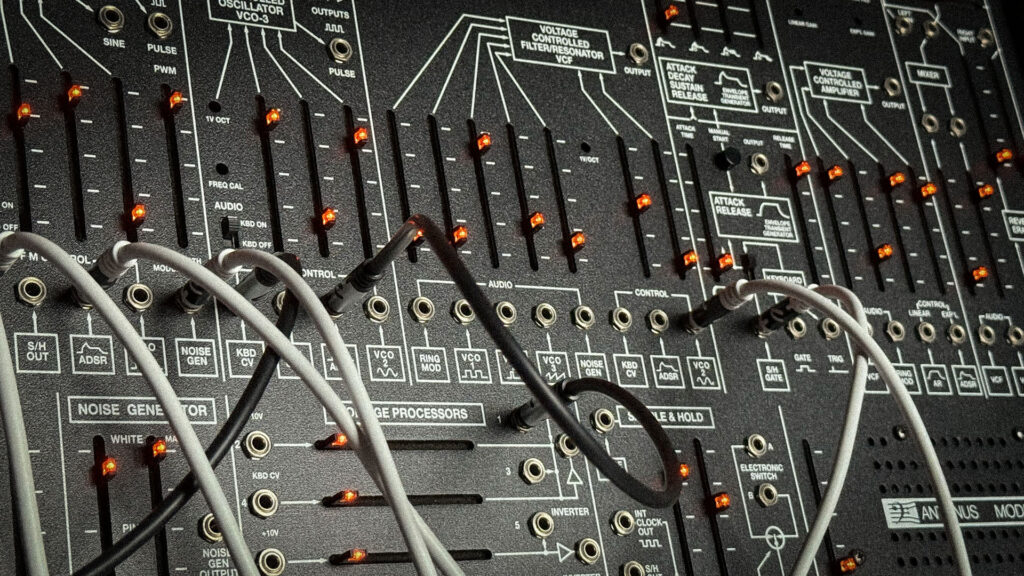

What Alan Pearlman created as a predictable synth for teaching was a beautiful alien that musicians immediately hijacked for purposes he never imagined. Take the filter resonance. Any competent engineer will tell you that a properly designed filter shouldn’t self-oscillate. That’s a flaw, an oversight in the gain staging. But the “flaw” gave us the singing, screaming, whistling heart of countless classic tracks. Push the resonance past 8, and suddenly your filter has become an oscillator in its own right, creating pure tones that can be played melodically.

In a world obsessed with the newest, fastest, most feature-packed tools, the 2600 through its imperfection reminds me that depth beats breadth every time.

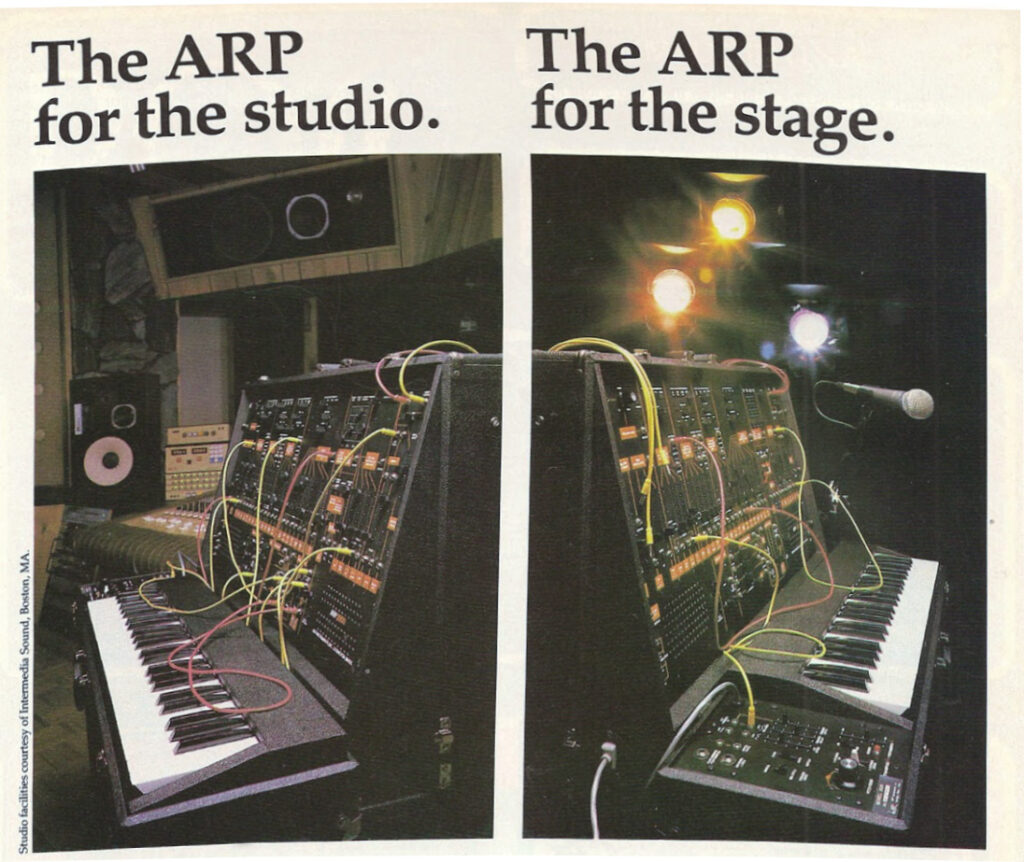

How a “Failed” Design Inspired Modern Freedom

In an age of algorithmic music, why are producers returning to this synth from 70s?

The answer lies in watching Lisa Bella Donna work. Her 3-hour improvisations are channeling sessions: she approaches the 2600 like a ouija board for contacting parallel dimensions. No predetermined sequences, no safety nets, just her hands on the controls and a direct line to the cosmos.

Here’s the thing about Lisa’s approach: she treats the 2600’s chaotic tendencies as a collaborator. When an oscillator drifts, she follows it. When the filter starts self-oscillating unexpectedly, that becomes the new tonal center. This philosophy represents a complete inversion of how we typically think about electronic music production. Instead of imposing our will on the technology, we become conduits for what the technology wants to express.

Tefty & Meems have also spoken about using the 2600’s chaos as a “fifth member” of their compositions – an active participant with its own voice and agency. Feed white noise into the sample-and-hold circuit, route that to oscillator pitch, and you have a generative system creating melodies you never could have conceived. What you want to do is stop thinking of these as random events and start hearing them as suggestions from a collaborative partner. The machine offers possibilities; your role is to recognize which ones serve the music. This requires a different kind of listening, a receptiveness to accident and coincidence that most modern production workflows actively discourage.

Orbital took this even further. Their otherworldly transmissions on tracks like “Halcyon” came from pushing the 2600 into territories Pearlman never imagined. Ring modulation – intended for creating bell-like tones in academic compositions – became a portal generator. Feed two oscillators into the ring mod, detune them slightly, and you’re creating frequencies that shouldn’t exist, sum and difference tones that place your sounds in impossible acoustic spaces.

Why in such a process are 8-minute tracks born so often? Here’s something most people don’t realize: the 2600 makes these extended durations feel compressed. When you’re truly locked into a patch, when the feedback loops between your ears and your hands and the machine achieve synchronization, time dilates. What feels like 30 seconds of knob turning reveals itself as 8 minutes on the recording. This is beyond mystical nonsense: a pure result of engaged, present-moment awareness that the machine’s immediacy demands.

Producers like these aren’t using the 2600 out of nostalgia.

Beyond Thinking: My Personal Story with the Antonus 2600

My pilgrimage started with a single YouTube video. Three minutes of someone playing an Antonus 2600, recorded with a phone, compressed to hell, and it still made my chest tight. Imagine the difference between supermarket honey and raw honeycomb straight from the hive. That’s the gap between every 2600 clone I’d played before and what I was hearing from this Spanish recreation.

Eighteen months. That’s how long the wait list was. Eighteen months of watching build videos, reading forum posts in broken English translated from Catalan, saving every penny while friends questioned my sanity. “Just get the Behringer,” they said. “It sounds the same for a quarter of the price.” They didn’t understand. This wasn’t about getting “a 2600.” This was about getting this 2600.

Kilograms of hand-built synthesizer, packed like a religious artifact. Every component chosen, placed, soldered by someone who gives a damn. The knobs turn with perfect resistance. The sliders travel like they’re on rails machined by Swiss watchmakers. You know how some guitars have “the note”? That frequency where the wood resonates perfectly, where the whole instrument sings? The Antonus has that, except it’s not one note. It’s a quality that exists across the entire frequency spectrum.

The 4012 filter deserves its own book. Antonus sourced the exact transistors, matched them by hand, treated each filter like a violin maker treats wood selection. The resonance sings. Push it, and it compresses in this organic way, like tape saturation but different. Feed it a square wave, crank the resonance to 9, and sweep the frequency slowly. That whistle got harmonics dancing around it, little ghost notes that appear and disappear based on input level.

I was working on an ambient piece for a game soundtrack – procedurally generated worlds needed procedurally generated music. I’d been fighting with Max/MSP for hours, trying to create evolving soundscapes that felt organic. Frustrated, I opened window for some fresh air, fired up the Antonus just to clear my head. Started with a simple drone, oscillators slightly detuned, filtering moving slowly. Then I noticed something: the room temperature had dropped (winter in Belarus), and the oscillators had drifted. Not much, maybe 10-15 cents. But that drift created this beating pattern that seemed to breathe with the room. I started recording. No plan, no structure, just following where the drift led. The colder it got, the lower the pitch dropped, the slower the beating became. I found myself playing the studio temperature as much as playing the synthesizer. Opening the window more sped things up. Closing it slowly slowed them down. The piece wrote itself over the next two hours, me barely touching the controls, just nudging here and there when the machine suggested a new direction.

The drift diaries became my new obsession. Every session, I document the temperature, how long the machine has been on, what the pitch relationships are. Patterns emerged. The machine has moods. Warm summer mornings, it’s stable, almost locked. Cold winter nights, it’s wild, unpredictable. Spring and fall are the sweet spots – enough variation to keep things interesting, not so much that it’s uncontrollable.

The Digital Handshake: Making Ancient Technology Speak Modern

How do you teach a 1970s veteran to speak fluent 2025s? Very, very carefully. MIDI integration impacts the fundamental analog nature of this instrument. The original ARP 2600s exhibit characteristic distortion as signal levels increase in the filter mixer and VCA that modern MIDI implementations struggle to replicate. Thus no modern model offers comprehensive MIDI parameter control expected in modern synthesizers. The inability to automate filter sweeps, oscillator tuning, or envelope settings via MIDI significantly limits integration with contemporary production workflows.

Behringer threw features at the wall hoping they’d stick, but those MIDI clock issues? I can’t tell you how many sessions are ruined by stuck notes and dropped triggers. The last thing you need is your synthesizer deciding to skip every twentieth note during important recording session. Korg went the opposite direction, and I respect the reliability focus. Their MIDI works every single time, no dropouts, no surprises. But they stripped it down so far that you can’t even send velocity properly.

That said, the Antonus implementation reveals something deeper about understanding what makes the 2600 special. Yes, the SysEx configuration is annoying – I’ve got mine permanently on channel 1 because who wants to upload files just to change MIDI channels? But once you’re past that initial setup, you’re working with transparent MIDI-to-CV conversion that actually respects the analog signal path. The duophonic capabilities with dual CV/Gate outputs mean I can play basslines and leads simultaneously, something the others can’t touch.

What you want to do is look at how each unit handles the fundamental character of the original. The Antonus maintains that characteristic filter overload when you push multiple oscillators through the mixer – that growl that made the 2600 famous. I’ve A/B tested this against vintage units, and the Antonus captures that nonlinear behavior in ways the Behringer’s voltage processor can’t fake. The Korg sounds clean and modern, which some people love, but that’s not why you buy a 2600. When I need that “Won’t Get Fooled Again” sweep or those Lisa Bella Donna cosmic drones, the Antonus delivers without compromise.

The money shot for recording: forget everything you know about modern gain staging. The 2600 outputs hot, sometimes very hot. Your instinct will be to pad it down, compress it, tame it. Don’t. What you want to do is configure your interface to handle the full dynamic range without clipping, then capture everything. I run my interface inputs at minimum gain, no pad, and let the 2600 fill up the meters. Sometimes peaks hit -3dB. Sometimes the signal barely tickles -20dB. That variance is the life of the performance.

If you’re interested in more nuance in comparison of the top-three modern ARP2600 options, here is a brilliant review by Tom Noise:

The hybrid sweet spot emerges when you stop trying to make the 2600 behave like a plugin and start using digital tools to unlock possibilities the original designers never imagined. Example: clock dividers in your DAW sending polyrhythmic triggers to multiple envelope generators. Suddenly your 2600 is playing rhythms that would require three pairs of hands to perform manually. Or use Max/MSP to analyze incoming audio and convert spectral peaks to CV, making the 2600 “listen” and respond to other instruments in real-time.

The bottom line is this: making ancient technology speak modern is about creating a conversation between eras, letting each side contribute its strengths. Together, they create a third thing – not vintage, not modern, but timeless.

The Spellbook: Seven Patches for the Modern Mystic

1. “The Cosmic Sweeper” – The filter sweep that makes grown producers cry

Start here: all oscillators off. Yes, you read that right. We’re using the filter as our sound source. Resonance to maximum, just before self-oscillation. Filter cutoff at zero. Now, LFO to filter frequency, but here’s the trick – use the inverted output. LFO rate around 0.1 Hz. Depth at 7. What you’re creating is a sweep that starts fast and slows down, like a gravitational pull.

The moment you know it’s working: when the sweep hits around 200 Hz, you’ll hear the room resonate. Not the speakers – the actual room. That’s when you know you’ve found the sweet spot. Record this with a room mic in addition to the direct signal. The acoustic interaction is half the magic.

2. “Organic Percussion” – Transform lifeless samples into breathing rhythms

Feed your drum loop into the preamp input. Not too hot – you want headroom for what’s coming. Route through the filter, resonance at 6, cutoff controlled by the envelope follower. Here’s the secret: mult the envelope follower output and feed it back to the VCA controlling the input level. Now the drums are playing themselves, each hit modulating the next.

Add the S&H clocked by the audio input, controlling oscillator 1’s pitch. Mix just a whisper of oscillator 1 with the filtered drums. Every kick drum triggers a new pitch, creating ghost melodies that dance around your rhythm. The transformation from static loop to living instrument happens around the 30-second mark. Trust the process.

3. “The Infinite Sustain” – The drone that plays itself while you sleep

Oscillator 1 as your fundamental, sine wave, low frequency – think cello’s lowest string. Oscillator 2 one octave up, triangle wave. Here’s where it gets interesting: oscillator 3 in LFO mode, very slow, modulating oscillator 2’s frequency just enough to create beating. Route all through the filter, cutoff at 3, resonance at 7.

The magic: use the ring modulator between oscillators 1 and 2, mix about 30% with the direct signals. The ring mod creates undertones that seem to come from nowhere. Set your envelope to maximum attack and release – we’re talking geological time scales. Trigger it once and walk away. Come back in an hour, and it’s evolved into something completely different.

4. “Vocal Aliens” – Turn whispers into transmissions from other dimensions

Your voice into the preamp, gain staged so peaks just kiss the red. Envelope follower tracking the input, controlling filter cutoff – standard vocoder territory so far. But now: route the envelope follower also to oscillator 1’s frequency. Set oscillator 1 to track at about 1/4 the rate of the filter. Your voice is now controlling two related but different parameters.

The revelation happens when you add ring modulation between your voice and oscillator 1. Suddenly you’re multiplicating it with itself. Whisper, and you sound like benevolent aliens, shout, and you’re summoning demons. The sweet spot is conversational volume with very close mic placement. The proximity effect adds bass that the ring mod turns into subsonic communication.

5. “Tempo Synced Chaos” – Controlled randomness that grooves

Clock input from your DAW, but here’s the twist – run it through a clock divider first. /7 works beautifully because it creates patterns that almost align with 4/4 but keep slipping. Clock drives the S&H, which controls everything: oscillator pitch, filter cutoff, VCA level. But attenuate each destination differently. Full range to pitch, half to filter, quarter to VCA.

Layer two of these running at different divisions (/7 and /5), panned opposite. What emerges is a conversation between random sequences that occasionally agree on downbeats. The groove is in the relationship between disorder and occasional synchronization. When it locks, you feel it physically.

6. “Deep Space Communications” – The patch that made my neighbor think I’d contacted aliens

Noise source to S&H, clocked erratically (use the keyboard gate, play random notes). S&H to oscillator 1 pitch. But oscillator 1 isn’t making audio – it’s in LFO range, modulating oscillator 2, which is modulating oscillator 3. Three levels of modulation creating frequencies that shouldn’t exist. Add ring mod between 2 and 3, filter the result with maximum resonance.

When you hit the right frequency relationships, standing waves appear in your studio. You’ll hear the sound moving without panning, creating phantom images that seem to exist outside your speakers. My neighbor knocked, genuinely concerned, asking if I was “receiving transmissions.” In a way, I was.

7. “The Living Bassline” – Bass that evolves like a conversation

Simple start: oscillator 1, sawtooth, two octaves below middle C. But here’s what makes it live: LFO to pulse width at a rate that’s slightly offset from your track tempo. If you’re at 120 BPM, set the LFO to cycle at 119 BPM. The phase relationship constantly shifts, making every bar slightly different.

Filter tracking the keyboard at 50%, so higher notes open up more. Resonance controlled by mod wheel – this is your expression controller. The final touch: route the audio output back to the mod input at very low level. The bass is now modulating itself based on its own amplitude. Play soft, it stays stable. Play hard, it starts to growl and shift. It’s not just responding to your playing – it’s commenting on it.

Each patch here is a starting point, not a destination. The exact knob positions matter less than understanding the relationships. When you find yourself making micro-adjustments, chasing some sound that exists just beyond the current setting, that’s when you know you’re in dialogue with the machine.

Letting Experience In

I believe, in 2025 the most futuristic sound you can make comes from 1970. While the world chases the next plugin, the next update, the next revolutionary digital modeling technology, a growing underground of producers has discovered that the future was already invented. It just took us fifty years to understand what we had.

Here’s the thing about AI and music production: it will never replace connection. When my Antonus drifts sharp on cold mornings, that’s my studio talking to me, the machine responding to its environment, creating a unique fingerprint that exists only in that moment. AI can generate a million variations of drift. It can’t generate THIS drift, happening NOW, in relationship with THIS room at THIS temperature while I’m in THIS mood. And the me-machine connection is not the only one to praise.

Trust me, the community around the 2600 represents something special in our fractured musical landscape. Go to any forum, any Facebook group, any Discord server dedicated to the 2600, and you’ll find something rare: genuine knowledge sharing without ego. Someone posts a patch question at 2 AM, and by morning there are three detailed responses, often with hand-drawn diagrams. Why? Because everyone remembers their first year with the machine, that feeling of staring at the panel like it’s written in alien script.

Here’s my invitation: find an instrument that scares you a little. Doesn’t have to be a 2600 – could be a modular system, a vintage drum machine, hell, even an acoustic instrument you’ve never touched. Something without presets, without memories, without safety nets. Spend six months with it. Only it. Let it teach you its language rather than forcing it to speak yours.

Some magic can’t be saved, only experienced.